Interview and photos by Elif Kahveci

More photos can be accessed here.

You've graduated from Istanbul Bilgi University, Department of Visual Communication Design (VCD). How did your understanding of design evolve in this department that comprises a variety of fields? How do you feed off of different fields?

I was a child that was always interested in various materials and fields; a curious boy who figured out what he wanted to learn and focused on that. During my time as a student at Terakki, I dealt with plastic arts, music, photography, literature, and physics projects as much as –if not more!– regular classes. Even though I wasn’t quite sure how these fields would come together in high school, I started to grasp the potentials of ‘multidisciplinarity’, a term we had only started to hear about, right when college began.

For me Bilgi VCD was a department of design in which I could get to know many fields around visual communication, and use them all together. If you are interested in more than a single field, school can turn into a playground that enables you to jump among faculties. While many schools enrolled students based on their works on paper with pencil, I was provided a superb environment to experiment. These experiments enabled me to establish a conceptual thought system both for my artistic and commercial works. It also helped me to know myself better and form a better professional self by making me feel which parts I was good in and which jobs I enjoyed. Sometimes we ask for a second set of eyes to take a look or require the opinions of someone who has no idea on the matter, right? This is because we know that person would approach the issue independent from our own learnings. Feeding off of different fields enables me to contain various points of view, and open up a variety of antennae for different people. As I’m interpreting an artistic word from a technical aspect or taking a geometrical look towards a work of graphic art, I feel like “crosschecking” the things I’m doing.

You attended border_less ARTBOOK DAYS and FLAT – Fiera Libro Arte Torino with your graduation project titled Balta, makas, çekiç (axe, scissors, hammer). Can you tell us the story of the book?

Balta, makas, çekiç is a design research on three hand tools that are slowly evaporating from Anatolian culture. Since I associated hand tools with production, cared about cultural documentation in general, and aimed to reintroduce these tools, I turned the project into a book and published it. My goal was to highlight these tools as a cultural value. I introduce the tool to the reader, and tell them about the function and morphological qualities of that tool, as well as the differences between them and transparent pages. I create a typology with the structural average of each tool, and present three dimensional models of this typological design as downloadable content.

The book also contains archaeological illustrations of the hand tools you focus on as your main materials. Why did you choose this technique over photographs?

It would have been so much easier with photos! I took photos of each tool throughout my research, but I only used them as reference. Those illustrations are one of the reasons it took months to finish this book, yet they were worth it. You cannot tell that they are illustrations; this is a technique called plotting or stippling. This technique allows one to create marks by leaving light dots with thin-tipped pens. Even though I felt that this technique was right from the beginning, I made up my mind when I came across archaeological illustrations. For a long time this technique was used in documentation illustrations which required intensive detail transfer. Many illustrators must have worked just like a dot matrix printer for years! I had to relay the structures of these tools as a technical drawing and make the smell of forged steel felt.

There was also a romantic side of it, which was something I noticed midway through the work. I was able to finish an illustration in an average of 7-8 hours. That was taking almost as long as a smith forging an axe before the introduction of modern equipment. The time I spend also makes me feel as if I am giving props to the real owner of these products.

Why are you so interested in hand tools? What is your personal motivation behind pursuing the Anatolian axe?

Hand tools are related with handicrafts and the human anatomy, and I’m interested in both. Every hand tool has a close relationship with the craft they are being used in. Besides their designs and materials are not that influenced by technology. An axe used in ancient times, and an axe that you can go buy now were designed for the same “human hand”. And the basic forms of these tools will not change unless the form of hands changes. I find this fascinating.

The story of how it all began is in fact quite personal and is the foundation of a project of obsession. While I was trying to find a topic for this project, which would be on my agenda nearly for the following two years, I had two encounters in a short span of time. One was in my grandmother’s house; a place I frequently visit to drive inspiration from. In this house which I had torn apart over the years, I found a small axe I had never seen before. What caught my attention was how different it was compared to what I had grown accustomed to with regard to axes. Later when I took a trip to the Thrace region with my friends from school, I started to notice axes with similar forms. The topic of my project was finalised towards the end of the trip when a friend of mine gave me the tools of his grandfather, who was a horseshoer, as a gift.

I knew that every geography uncovered its own hand tool forms, and Anatolia had its own tools. I could not find any projects that focused on this topic, and started doing the first one myself. I travelled, took samples from craftsmen and museums, talked to people, prepared illustrations and 3D models. This marked the beginning of a work on typology and denomination, even if it was only for three tools. I wanted to publish the book with an ISBN number, and bring the terms of Anatolian curved carpet scissors and the Anatolian shoeing hammer into literature. This way they could be remembered even if they were lost. I feel I got closer to this goal with the English edition I prepared for the International Art Book Fair, which took place last November in Turin.

Following the mass production craze, the maker culture is becoming more and more widespread. How would you evaluate the notion of ‘democratised production’? Do you define yourself as a maker?

Some production techniques that used to be only implemented in significant production facilities, such as laser cut, 3D print, and various digital production methods are now accessible in small businesses and households. There are a number of options for those who wish to create; we have grown accustomed to this over the past few years. I think Turkey has a special place with regard to this issue. In addition to being a country that can quickly adapt to technology, we have a culture that is eager to help. You would know those carpenters in the neighbourhoods our parents talk about, or the turners stuck between cafes in Karaköy, patiently helping out design students. I don’t remember any craftsmen or relatively big business owner turning me down. A metal processing workshop in Europe would not stop their production of thousands of pieces just to do your work of a few pieces. Yet this is a country full of curious people and production was always democratised here! The important thing is maintaining the continuity of the thing you are producing and turning it into a brand.

Yes, I can define myself as a maker. Different materials and production methods excite me. I feel like everything I want to do is within reach and that is enough for me.

Can you tell us about your relationship with materials and how this affects your understanding of design? Which materials do you prefer and why?

As a kid my favourite TV content was –maybe it still is– Discovery Channel’s How It’s Made. Seeing how daily objects were produced introduced me to the relationship between design and engineering. Meanwhile my mom constantly used to find new materials and books that would make me even more curious. Since those years I’ve been trying to guess how most objects that I come across are produced and wonder about their past. This practice was reflected onto every field I’m interested in.

When I started doing printed works, I looked into how printing houses work and how paper was produced. When I developed an interest for bikes, I took old bicycles and restored them. Adopting an inductive approach and reverse engineering the topic I’m working on resembles grasping the grammar of a language you are currently learning. Do I need to produce a revolving mechanism for a sculpture? Then I can observe record players. Am I doing the brand identity for a company in the textile sector? Then I need to see how they generate their products.

The materials change according to the specific work and time. But I can say I’m quite fond of the 1980’s hi-fi system aesthetics. Brushed aluminium, transparent pieces, and a little light… Then again since I’m doing a lot of printed works these days, I’m currently buried in paper!

There are also some printing techniques that are apparent in your designs. One can observe that you are into analogue production. Can you tell us more about the thought behind the aesthetic created by the flawed look in some of your work?

Printing methods are one of my primary concerns. When I was a little boy I remember being extremely impressed by the engravings I saw in a museum I went with my parents, and trying to copy those thin lines in order to draw similar engravings as soon as we got back home. Later I became interested in machine printing techniques. For instance, back when we were juniors in high school, I insisted upon printing the invitations for our first co-exhibition –with my close friend Kaan İşcan– using an offset printing machine. My only concern was to make up an excuse to see the offset technique.

Since we received a relatively digital education in college, I was not able to work with conventional methods such as serigraphy. Working around a small field pushed me towards trying out techniques that were “less messy”, such as doing laser engraves on linoleum plates and making small printing blocks out of stamp silicones. That “flawed look” you mentioned was one of the effects I went after. Old postcards and packages always had an influence on me. There are colorimetric shifts and contaminations in the prints which are made using the means of their respective time. Once you pay attention to this, it is something that cannot go unnoticed. I believe those “mistakes” make each print unique. You can feel a human’s touch. Later I came across the Japanese Wabi-Sabi philosophy, and started embracing the flaws of certain prints. This can also be seen in a recent print work I did using paper bags of nut sellers I had been collecting for some time.

In addition to your personal projects you also do commercial works. How do you balance your design and art works while separating them as commercial and personal? What are the challenges that get in the way?

Everything I ever did began as a personal project, or as a project of curiosity, of passion. Some of them merged with my personal life to become my works, and enabled a never-ending tight relationship between my personal projects and commercial works. For the past three years I’ve been doing works on visual communication design and providing consultancy services in my own studio. I do works that come and go between brand identity, products, prints, and graphic design. Designing brand identities is also a field that raises my will to work, since it incorporates a variety of applications. These projects are usually shaped around long-term goals and sustainability. I also do installations by collaborating with different venues and events.

The basic work dynamics are sometimes similar, and sometimes quite different. What’s different in visual communication is that creative industries have low recognisability. Design requires a serious effort in background, communication, time, and thought. That is why I patiently try to explain the theory behind some works. I see design as a living job that thousands of small decisions reach to temporary solutions by quickly being shaped by serious foundations and theories of perception. When someone comes up and says “Let’s make this green, instead of red,” you become obliged to explain it. I would have loved to be an architect and say “No way, it would mess up the statics,” when something like this happens!

Together with four other artists you did the installation titled No. 8, as part of the residency programme at Zorlu PSM with the collaboration of Digilogue and British Council. Your kinetic sculptures titled Fenakistiskop: Istanbul and Taumatrop: Loop were featured in the İllüzyonoskop exhibition at Gaia Gallery, and then at Sónar Istanbul. Would you be able to tell us more about these works? How did you develop a liking for kinetic sculptures and where is this interest headed towards?

No. 8 was a delightful project. We got together with 12 artists as part of the AltCity Istanbul programme, and produced separately over two weeks. No. 8 is a kinetic sound installation created as part of this programme in collaboration with four artists. We had eight motorised platforms whose movements were designated in accordance with a code sequence adapted from a graphic notation, and a sound scheme that took sounds from these moving platforms and gave it back to the room it was built in. Inside the platforms were found objects of Istanbul such as broken pieces of glass or spalls, collected around Zorlu PSM. It was a chaotic experience of Istanbul sounds.

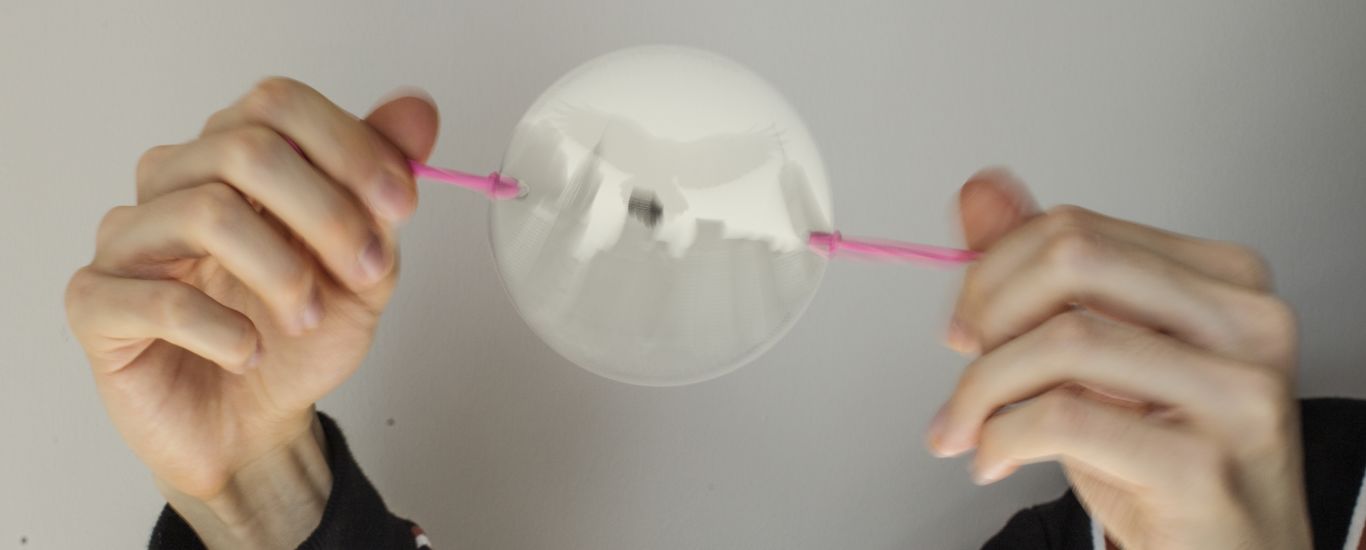

Fenakistiskop and Taumatrop are part of a series of “analogue screen” we started producing with Deniz Derbent, which utilizes the principles of optical illusion. Fenakistiskop is a kinetic sculpture which changes the 12 animated frames engraved in its disc into moving images by synchronising it with motion and light strobes. Taumatrop is a completely analogue machine that similarly generates two-state-animations. The discs, or their animations or narratives, can change from exhibition to exhibition. These works are hard to define, I would want everyone to take a look at their images and videos. I’m interested in these kinds of productions because they contain an utter sense of togetherness with regard to different disciplines. Media arts require the association of fields such as production, electronics, optics, and physics, in addition to people from various disciplines. With the synergy of all these, one is able to create eccentric machines that tell different stories!

Can you tell us about what you’re currently working on or your works yet to come?

I’m preparing on two exhibitions for the upcoming months. Other than that I’m also working on a product series I plan on releasing in early 2020. I’m one of the resident artists of The Istanbul Biennial Production and Research Programme. We will go on working at İKSV with 14 other artists until spring 2020. In addition to these, other visual communication design projects will surely be on my plate.

Click here for Ufuk Barış Mutlu's personal website, and here for his Instagram page.