Interview and photos by Elif Kahveci

More photos can be accessed here.

Following your undergraduate education in Istanbul Bilgi University’s Department of Architecture, you received a master’s degree in London with your thesis on the Florya Beach and the modernisation attempts in Turkey. Can you tell us a little bit about your thesis?

In my thesis, I dealt with the Florya Beach as a part of the modernisation process in Turkey that took place after the proclamation of the republic. I tried to study Florya Beach, which seems to be shaped in line with the time in which steps were taken to transform the society, using the media images of the time and family photos I found from eBay. So I can say that my research feeds on material culture, and focuses on the tension between how the beach is represented in the media and how it is used in everyday discourse. For instance Atatürk’s summer house, which constituted an example of modernist architecture, was there, and this strengthened the symbolism assimilated with the beach. I linked the constructional activities –structures such as casinos and summer houses– that took place until the 1950s with the everyday life and leisure time, which had changed between 1930 and 1950 as a result of the state policies. Either way, I believe I could have approached the issue differently if I was writing my thesis today. I am not sure whether social change can be directly controlled and shaped to this extent.

You mention a city image in your essay on Frankfurt. What do you think is the image of a city? How is it formed?

The city image is directly connected with capital and politics. Cities can sometimes be referred to using certain keywords, and constructional and touristic activities are associated with these words. This created image leads to the city being marketed in a way, with terms such as city of finance, city of gastronomy, etc. Then again when you stay in a place somewhat longer, you begin to see it through a newer perspective, one that is quite different from the preconceived image on your mind. Media plays a critical role in this created image, since photographs or other visuals of any environment are easily accessible through mobile applications such as Instagram. Going to that place and ‘experiencing’ it in order to legitimise the preconceived image on our minds, especially photographing and releasing it has become almost a fetish. For instance, in order to capture the image on our minds, we have a tendency to take photographs of the structure, and keep doing it with the same angle. On the other hand, touristic experience, which can be defined through visiting particular grand structures, has changed today. Being a tourist is almost looked down on. In order to become a ‘real’ tourist, you need to act ‘locally’; the initiating idea is mostly visiting where people who live there go to, and keeping away from tourists and touristic places.

How does the city image incite a transformation within the city? What may be the ways to disintegrate the city from its image in order to get to know it better?

‘Star architects’, for instance, are one of the biggest tools of this transformation. The relationship between Bilbao and Guggenheim Museum is a common example in the literature around architecture. When a landmark structure is set in a place, that structure is discussed with reference to it adding (or not adding) a touristic and transformative value. Following these processes, the city starts to be marketed in line with the image of the constructed building. The ‘signature’ buildings of these ‘star’ architects do not always present a peaceful and reconciliatory relationship. This is why I find it important to elude the preconceived image on our minds and to see it through a critical perspective when we visit a place, and to perceive and discover it in its own time, on foot, without planning beforehand. As the dérive theory developed by the situationalists in the 1970s suggests, letting yourself go in the city and letting coincidences come into play, as well as strolling around leisurely without any particular route or aim makes it easier to discover the city –perhaps yourself as well– and to establish a special bond with it.

Can we hear more about the research you did in Brick Lane, London?

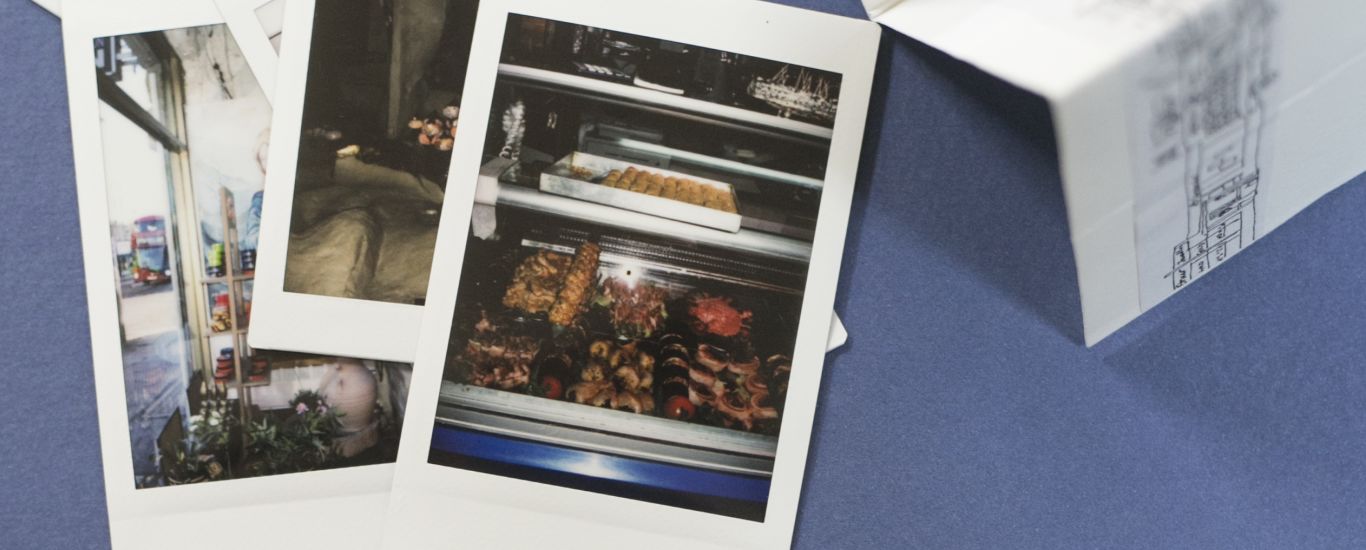

Brick Lane, located in the eastern parts of London, is an area which attracts many tourists with its restaurants, night clubs and streets full of graffiti. The ‘cultural capital’ accumulated as a result of the Bangladeshis and other ethnicities living here has been used by the local London authorities; this part of the town has been transformed since the 2000s as a way of acquiring unearned income. These decisions have enabled many restaurants, shops, food markets, festivals to be set up in Brick Lane as places to spend leisure time. This transformation led to current practices being commodified and turned into a mean of consumption, and this was what caught my attention throughout the research. As a result, the ‘culture’ of the community that resides here can only be visible under the conditions defined by capitalism. Going to those neighbourhoods and shopping there, attending the events and eating local foods have all become touristic activities.

Does Istanbul feature any projects of gentrification in terms of cultural capital?

Even though they are not exactly the same with Brick Lane, I can think of Karaköy, Bomonti, and Kadıköy-Moda. These were once residential areas, and many cafes, shops, markets were set up over the years. Yeldeğirmeni, for instance, features street art as a ‘revitalisation move’, much similar to Brick Lane. Neighbourhoods and their residents may find this transformation inevitable, yet local authorities have the power to prevent, rearrange, or positively change these.

How did you decide to stay in academia?

I love learning and researching. Academia can provide an environment in which one can do these creatively or at least think about them, while also running into others who do so. I also found out after graduating that working conditions, how young labour is situated in an office environment, and what one can produce as an employee was quite different than what I had expected. I believe academic work enables one to create outside of this system. Then again I do not think that practice and academic work are mutually exclusive. Critical thought should be a part of any creation; we may witness things change for the better, for instance, if architectural firms can accommodate research departments or if most of the people in academia can actively produce. This ‘practice’ does not have to be confined with designing and building structures; it may very well be a book design, for example.

What do your current thoughts focus on? What are you working on or reading at the moment?

I am currently working on a draft for my doctoral thesis at ITU (Istanbul Technical University). It basically is shaped around the relationship between travelling and architecture. Therefore my research so far has focused on guide books and works by scholars such as Urry MacCannell, McLaren, and Lasansky. I also have some more projects that are yet to be realised.

One of the two projects that I would like to do the most is producing a local gastronomy map in Northern Cyprus. This has been shaped in my mind while reading the gastronomy issue of beyond.istanbul, the publication of Mekânda Adalet Derneği (Center for Spatial Justice), and Slow Food Revolution. The other project I intend to actualise is a research which will attempt to investigate the process of destruction and urban transformation around Bağdat Avenue in Istanbul through architectural representation tools such as sketches.

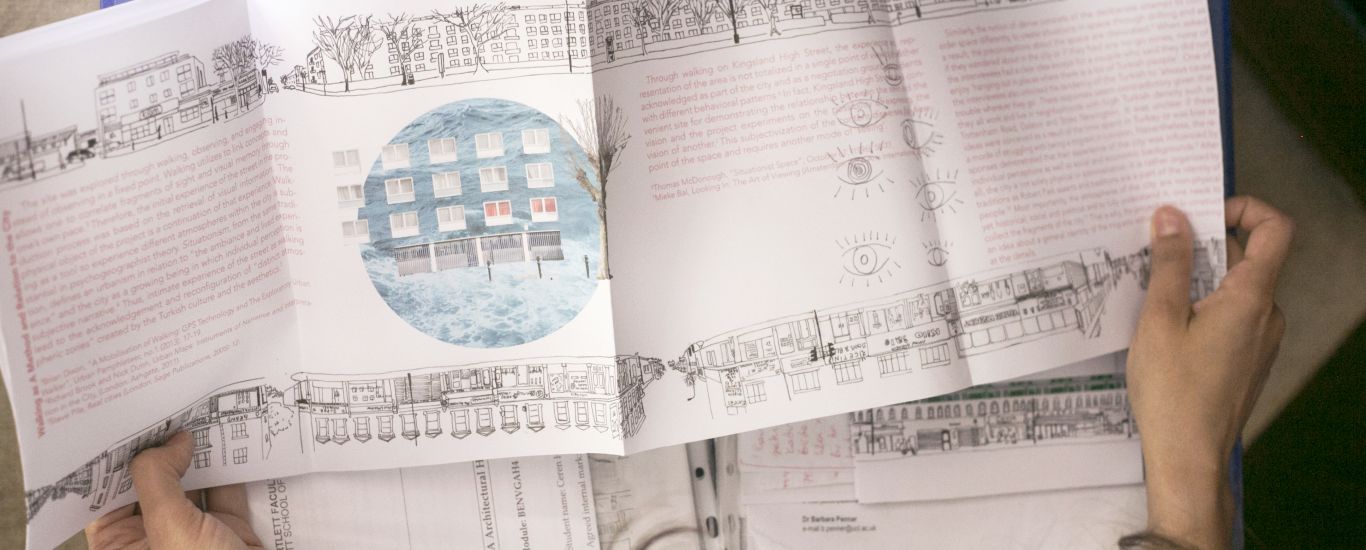

Can you tell us a bit about the project you led in Kingsland High Street which focused on the shopkeepers from Turkey?

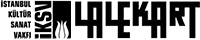

I had already produced another version of the Kingsland High Street project during my master’s education, in one of Jane Rendell’s classes. The project appeared within the scope of the term ‘site-writing’, as theorised by Rendell. The term can be defined as a way of rethinking concepts such as subjectivity, writing, and site-specificity; creating (or writing) a new place (or site) by using the relationship between places and subjects in order to redefine or rediscover spatial relationships. My work dealt with Kingsland High Street, an area located in Hackney in which migrants from Africa and Turkey mainly reside, and where there are many shops owned by Turkish residents. I discussed a number of issues with shop owners and employees such as what it meant to be someone of Turkish origin in London, working conditions, politics, tactics they have developed to simply exist in London as a shop owner or citizen, and gender roles. What came to light was a mixture of drawing-collage-writing. I really like the drawing part of the project since I feel it truly represents the façade. I had documented every building on the street before talking to the people in the shops. When we take a look at the drawings, we enter shops of which we know little to nothing about, and the real topics of the research –migration, citizenship, nationalism, subjectivity– run deeper at the ‘venue’ that lies between the two fronts of the street, with quotes from the interviews and the written piece that accompanies the drawing.