For centuries, women have produced knowledge and experience in a variety of ways. However, the man-centered understanding of science has triviliazed women’s experiences within the main narratives. (1)

1: N. Gamze Toksoy, “‘Dünyayı Yeniden Dokumak’ Shiva ve Mies’den Ekofeminizm” (“‘Re-Weaving the World’ Ecofeminism From Shiva and Mies”), Fe Magazine 13, no. 1 (2021), 101-106.

Who are these women?

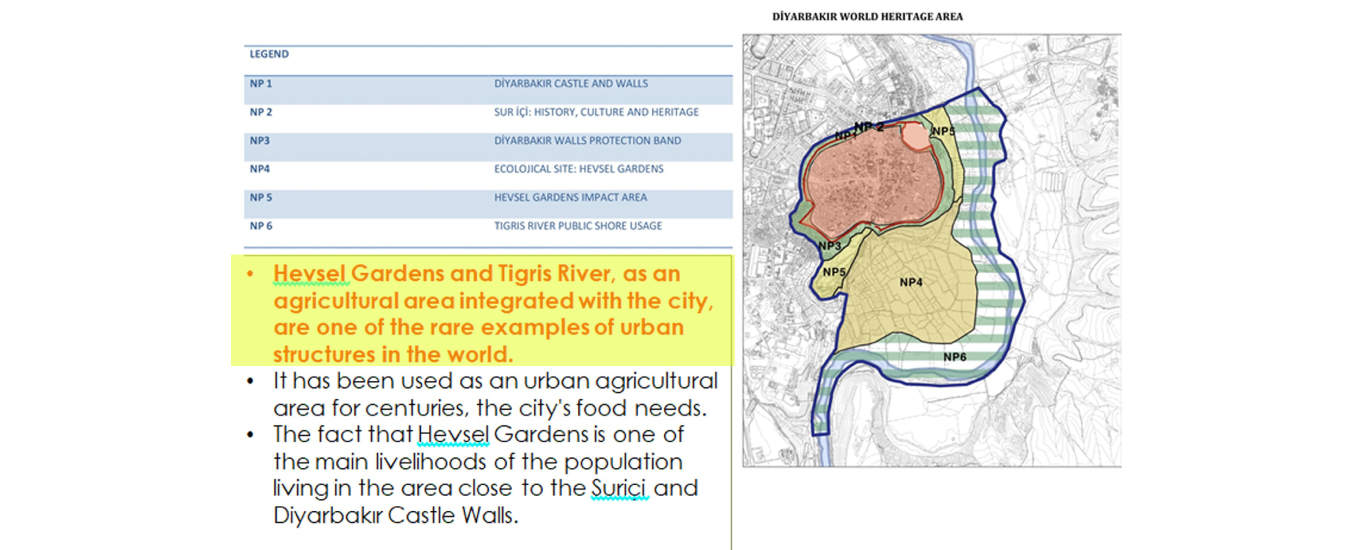

- I have crossed paths with the women workers of the Hevsel Gardens.

I saw these women as I was walking across the Suriçi district of Diyarbakır. Two women sitting on the ground… plastic bags laid in front of them… plastic bags full of sweet fragrant herbs…

- What are these fragrant herbs? Mint? Pennyroyal?

One of the women turned toward me to answer my question. As she turned, I noticed something on her back. Two loops stitched with white thread on her maroon waistcoat…

She must have tried to stitch the tear on the back of her jacket. Who knows, perhaps it was the load on her back she had tried to stitch…

- What was it that so compelled me? Something like a flash, even though I had passed through the same spot countless times before… Who were these women?

- A voice: The Women of Hevsel! The Mother Earths!

Mother earths, yet city-dwelling women who came to the Hevsel Gardens in the early hours of the mourning and spent the whole day in the fields with their families, women who raised their children in the fields and lived in the neighbourhoods surrounding the city wall. Women of all ages and backgrounds, some working their own ploughs, others seasonal or temporary workers, local or refugee, tradeswomen added up among these women who worked as agricultural labourers and earned a living from selling whatever they picked from the gardens in the historical intramural neighbourhoods of Diyarbakır. Refugee women who had migrated from villages to the city, away from the Syrian war, speaking diferent languages, possessing different cultural backgrounds, dwellers of the impoverished neighbourhoods, casual worker women, Mother Earths!

The city of Diyarbakır, which for years has continuously appeared on the agenda as part of a region associated with violence, therefore sticking in the public’s mind as such, actually teaches us new social data through the variety of user identities and storylines that have evolved as a result of the war and of the forms of resistance that have surfaced in its aftermath. The invisible forms of resistance that exist in this area where life is connected with nature, within a city known only for being part of a violence-torn region, are proof of the crucial necessity of reexamining the notion of resilience with the help of these women actors. The struggle given in the field, the struggle they give while selling what they harvest from the fields, the struggle they give dealing with the middlepersons, the struggle they give against the masculine ruling power.

Is it possible to look at how poorly visible the struggle given in the field by these women actors living at the intersection between the city and nature is, at how crucial it is for this struggle to gain visibility, at the production praxes of the working women of the Hevsel gardens, at the relationship they have formed with nature, at the modes of co-organization they have developed thanks to nature, at what nature has taken from them, at what they take from nature and at the channels through which we observe all this through a different perspective, with the help of the ecofeminist theory, and to grant visibility to the roles these women play in, the contribution they make to social life?

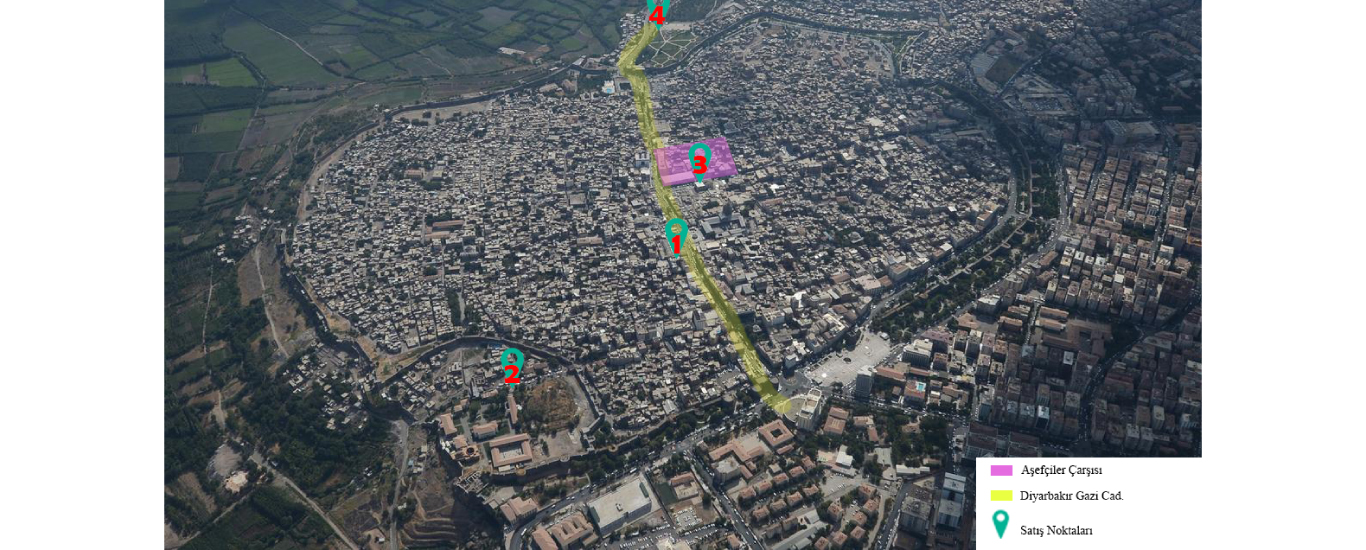

The Hoeing Women

In Turkish, the meaning of the word “Aşef” (“hoe”) encompasses all the gardening operations such as sorting out the remainder from the sowed saplings or the sowing itself, and the women who perform these operations are called “Aşefçi” (“hoers”). Within this culture that took shape on the basis of the sale of the garden crops, this term is mostly used to designate the women who sell in the city the crops and herbs that they pick from the gardens. The hoeing women, who are paid a daily wage in return for their work, are also traditionally granted a right to pick up the remainder of the crops, those that are too spoiled for the garden’s owners to sell on the market. The crops that are left over unpicked after the harvest are also granted for the hoeing women to collect. These were called “Xerat”. As the hoeing women started to work in the early hours of the morning, their shift would end by noon and they would pick up the fruits and vegetables left for them by the owners as well as the herbs from the Hevsel gardens such as basil and purslane and carry them in baskets on their backs to the hoers’ market in the Balıkçılarbaşı district of Diyarbakır to sell in the afternoon.