We met with Bodin Hon and Dilara Kan, founders of the Hong Kong-based Yellowdot Design Studio, which brings together culture, technology, science, arts, and crafts.

While we were checking out your work we saw that nearly all of them gained new contexts within this new paradigm and all were quite relevant to this day and age. How does the current situation force designers and design collectives to develop new methods and approaches for the problems of the world? Can design help us approach the current global crises in a different way?

Bodin: We try to do things in a more future-oriented way without being futuristic. Each of our projects are based on research about what is to be expected in the next five or ten years considering current issues and behaviours. Of course we did not predict such a major crisis like this, but exploring ways of being more efficient, sustainable, healthy, flexible and less wasteful were always important for us to create design that can remain relevant to people in many years to come.

It is a good time to reflect on certain mistakes and an opportunity to change them. We have been on an unsustainable path with regard to our wasteful nature with our resources. Before, it was almost very difficult for society to change their idea about working from home, but from this period we learned that rules, habits, behaviour can really change. For designers, this time of chaos opens a lot more room for exploration into new ways of thinking.

You can save a lot of time and be a little less wasteful when you cut back on commuting, but working from home is not perfect either. We always look at people, how they do things, why they are reluctant to change, and how they can adopt to new ideas.

Do these changes excite you or concern you? Or a little bit of both, maybe?

Dilara: We were very concerned in the beginning but we are also trying to adopt an optimistic approach and find ways to be excited about the future. As designers we can play a positive role in creating a better future going forward.

Bodin: Many periods of great uncertainty and struggles in the past yielded in leaps of innovation and changes. This is what is interesting to us and it overrides our current concerns. It’s also frightening as there is a possibility of our future slipping out under us if we don’t pay enough attention and continue with inaction. But as designers we try to do our part to provide positive solutions for the future. We hope we can be on time and deliver the ideas to the right people so that we can work towards a better direction after this.

Dilara: People’s psychology is affected as well. They cannot go out, socialise, or really share anything, so we’re also trying to improve our ways of communication in different formats.

One can observe a diversity in your personal and professional background. Dilara is a graduate of Marmara University Faculty of Fine Arts and Bodin studied engineering before entering the field of industrial design. How do your different backgrounds come together within your works?

Bodin: It’s all about our contrast, we are polar opposites for almost everything. I’m more serious, Dilara’s more fun. I’m more into the technical details, technology and manufacturing. But coming from an engineering background, I realised early on that design covers much more than these, and that is how our partnership started.

Dilara: I’m more into emotions, feelings, colour, and how they will be perceived by our audience. On top of that we aim to bring an element of joy and surprise to all our projects.

Bodin: In the end design is about solving human problems, which are never straightforward. People are complex, they have so many levels, and beyond the function of an object we consider how it fits in their lifestyle, taking into account their needs, behaviours and aspirations. Each of our designs goes through many different reviews by both sides before it is finalised. So you have at least two sets of opposing eyes looking at everything, and if it passes both of us it will hopefully be good enough for clients and people. (laughs)

Dilara: In the beginning we were of course fighting a lot and trying to understand how each other work. I always talk through emotions and feelings, so I would start a sentence by “I feel like…” and Bodin would go “…please prove it?” As if it was a math problem. (laughs) Every day in this world is already a new challenge, and working together is another one, but it is also what makes us better.

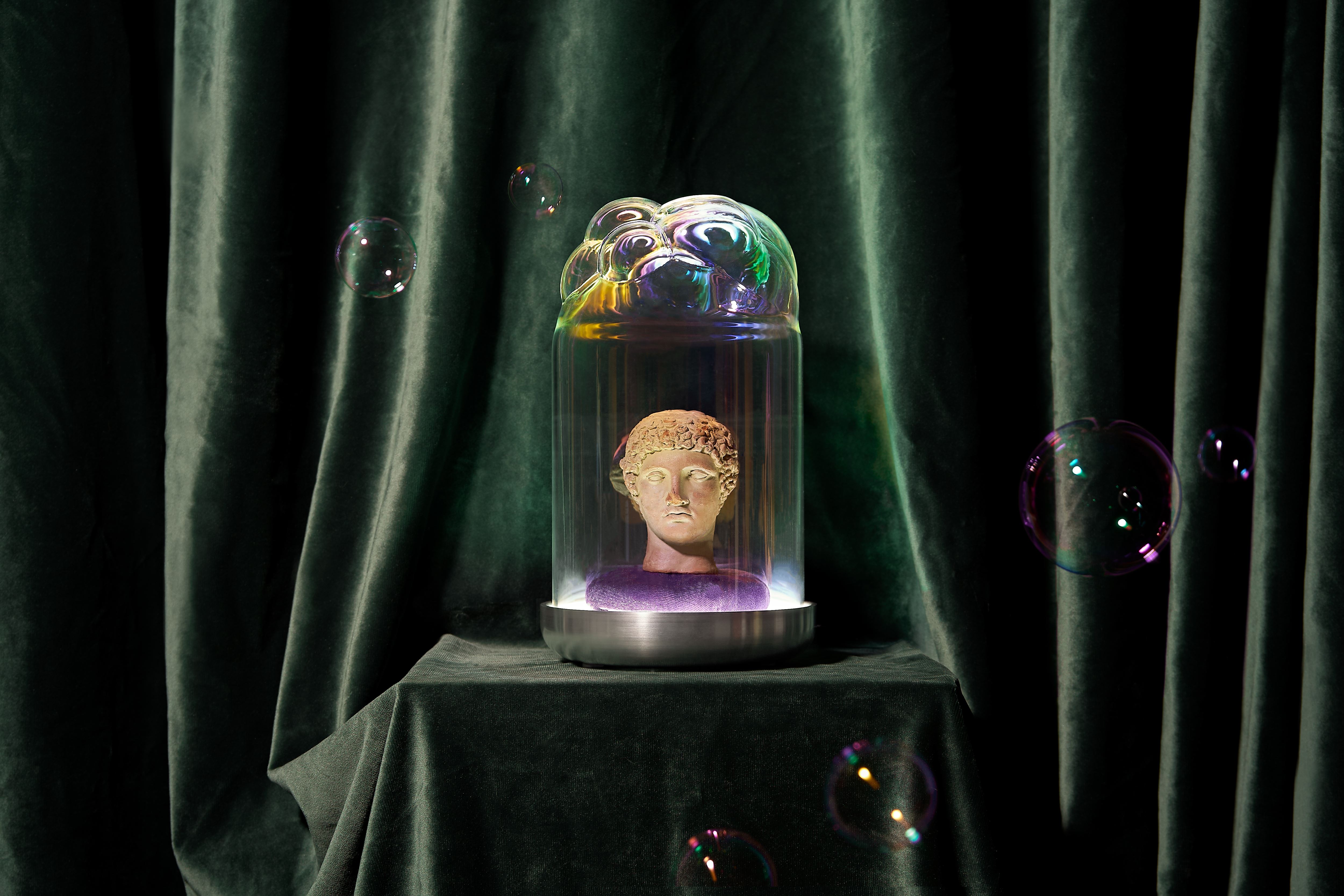

In a former project titled Memento, you dealt with the notion of objects that create memories and stories. After Yan Lianke’s lecture on communal memory, the issue of learning from and treasuring the past has gained a new context. Has the project gained another level of relevance in line with these discussions?

Bodin: We started this project because we saw that people were becoming more forgetful, regarding big crises like this but also small things in everyday life. The fires in Australia happened only a few months ago and I think most people forgot about it. We were looking into why this was happening and what was causing it. We learned about how we have “outsourced our memory” with technology. The internet has changed how we remember things – technology is great, but the downside is that not a lot of knowledge is retained, causing all this forgetfulness. What separates us humans is the ability to remember – we take our memory for granted.

We are also kind of between two generations in the sense that we have also experienced the start of internet, when things were much slower. Now, because there is so much information, it’s hard for someone to know what is important, remember those important things and put them in perspective. That’s why we wanted to find new ways to help preserving memories, especially happy ones which people always tend to forget. We found physical objects to be very strong as tools of memory and wanted to further explore them.

Dilara: In a way it resembles heritage. For instance your grandparents give you a box that you open 10 or 20 years later, and you can vividly remember with the help of those objects inside.

We are exploring that relationship between objects and memory. The sharing part of the project can also be considered as performance art. We make bubbles. On the surface it is fun and joyful, and something we are all familiar with from our childhood, but its ephemeral nature also adds to the visual metaphor of bubbles throughout art history to represent the transient nature of life.

Bodin: We’re also looking at why the past is important for the future. Today people don’t really value history as much. Lianke’s article mentioned how everyone remembers SARS from 17 years ago, and that’s why they were prepared in a way. Without memories you cannot create empathy and prepare for the future. We have to find some ways to remember and share what we have learned from the past more effectively.

You produce new kitchen tools with a sensitivity towards a more sustainable environment. Can you tell us a bit about Solari and Joyoung K?

Bodin: Both of these projects are also based on the past. Solari started with the idea to find new ways for outdoor cooking. Right now we have many problems such as the pollution caused by charcoal or fires being started in the forest. During the research project we found that solar was a non-polluting, safe and viable way to cook. The goal was to utilise this technology in the modern world as we found out that this was not the first solar cooker. It was actually quite popular in the ‘50s in the US with the hippie movement. They also had a few experiments in the 17th century.

As we said earlier, people just forget things. This is a good technology, but when oil is cheap and people are more into fast solutions, they go further down the road into whatever is more convenient. Now we’re facing this ecological and environmental crisis. So this could be a good time to reintroduce this technology in the modern world. We also changed the structure, used modern production techniques and lightweight materials so it’s portable and appealing. We also used the latest wireless sensing technology to monitor the cooking temperature in order to instruct people about how long they should cook something.

Dilara: We did some of the prototyping in Galata, then went around to do some demonstrations and talked to people to try and understand the market, but ultimately realised that the market was not quite ready. This was three years ago. Every year we see someone emailing us and asking about the project, so we are also trying to improve it, create different recipes and find the right partners to market the product.

Bodin: I was reading a book by Bee Wilson called Consider the Fork: A History of How We Cook and Eat, which tells the history of kitchen tools. The way of cooking is one of the hardest things to change because people have always done it in a certain way; traditions are difficult to overcome. At its launch, even the gas cookers had a very difficult time replacing the polluting, slower and more expensive “coal range” due to various suspicions and oppositions from the public regarding poison and explosions; it took almost half a century for wide adoption. If we develop the project and find the right recipes to cook with it, as well as the right people to use it, solar cooking may just work in some places. Beyond the design and manufacturing, we will also have to overcome certain cultural issues, which is the biggest challenge for innovation.

Joyoung is a client of ours whose machines have been around for many years. They make appliances that are like coffee machines, but for soy beans; they automatically grind and make homemade soy milk. Soy milk is actually one of the national drinks of China.

Dilara: Like Turkish coffee. Very cultural.

Bodin: It’s a very healthy and plant-based milk that is becoming very trendy in the West as well. We basically helped the client develop new ways to make the machines easier to use, turned them into more appealing and convenient objects so that young people like us can easily make healthy and nutritious drinks at home. The demographic used to be restricted with middle-aged housewives, so we helped them make a good product more appealing to a wider audience.

Dilara: We had to think about the particular culture, lifestyles, habits, etc. It was a big project.

Bodin: Instead of making something just beautiful, we wanted to integrate it with the lifestyles of people. In Asia beauty is less about cosmetics; it’s more about inner health. So a healthy drink made by an attractive machine that fits their modern home would definitely we popular among the people there.

You also create new forms of spatiality based on sharing and affections. How do these concepts apply to your works?

Bodin: I guess our way is creating some joy and surprise through the things we do.

Dilara: There are thousands of different types of furniture, of everything. We always question a different aspect we can bring and try to improve ourselves. We love this energy in humans, and that’s why we are called Yellowdot; it’s amazing when you see the Sun! We think really seriously, but act in a fun way.

Click here for Yellowdot's website.